I’ve Got the (Movie) Magic in Me: Costuming, Cinematography, & Changed Endings in Danny Devito’s Matilda

a short essay about my all-time favourite book Matilda, & how its movie adaptation proves through its costuming, cinematography, & ending that sometimes the movie can be just as good as the book

One of the most timeless debates lies in which is better: the book or the movie. Roald Dahl’s adapted works are not exempt from this deliberation, especially those concerning his most famous novels such as Matilda. This debate is inherently inequitable as the two are vastly different media forms; nonetheless, it is naive to negate that cinematography can provide added depth to the original story and its characters. Danny Devito’s 1996 motion picture Matilda achieves this as while Devito stays relatively true to Dahl’s narrative, his cinematography visually illuminates and nuances Dahl’s characters in a way that the book can not. Moreover, Devito puts his own twist on the tale by changing Matilda’s powers and altering the original ending. Although adaptations are notoriously hit or miss, Danny Devito’s 1996 Matilda highlights how film can emphasize textual characterizations through costuming, establish power dynamics through cinematography, and reinforce through Matilda’s revised powers and reworked ending that new is not always negative.

While books can describe appearance and clothing through writing and illustrations, movies allow directors to play around with costuming and viewers to recognize wardrobe patterns. The illustrations in Dahl’s books are characteristically drawn in black-and-white which works to exemplify Dahl’s theme of characters being inherently morally good or morally bad, but limits characterizations made possible with colour.

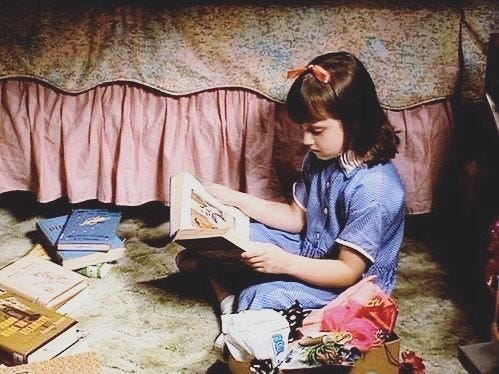

Devito utilizes costuming and colour theory in his film Matilda by crafting each character with a uniquely distinct colour palette. Viewers are introduced to a young Matilda who is a blank slate for her parents to project upon, symbolized through the white onesie that she wears as an infant in her opening scene (Devito 00:00:52).

As she grows slightly older, she is purposely dressed in pinks which highlight her mother’s attempts at raising her as an ultra-feminine ‘mini-me’ of herself (00:02:42).

Although her mother’s influence continues upon toddler Matilda’s pink dress, the narrator describes that Matilda has “developed a sense of style” as she ties a blue bow around her hair—the opposite of pink and of her mother.

This narrative moment represents a symbolic and intellectual departure from parental control as hereafter, Matilda swaps out her inconspicuous blue bow by confidently committing to fully blue dresses (00:03:13). Devito continuously dresses Matilda in characteristic blue shades to symbolize her intellect, wisdom, and imaginative spirit along with whites to convey Matilda’s childlike innocence and purity that she longs to keep but is constantly threatened by her parents’ carelessness.

Near the end, her palette expands to include more playful florals—mirroring Miss Honey’s wardrobe—and sunny yellows to suggest her newfound optimism and bright future. She no longer feels confined to mature blues or pressured into pinks by her parents.

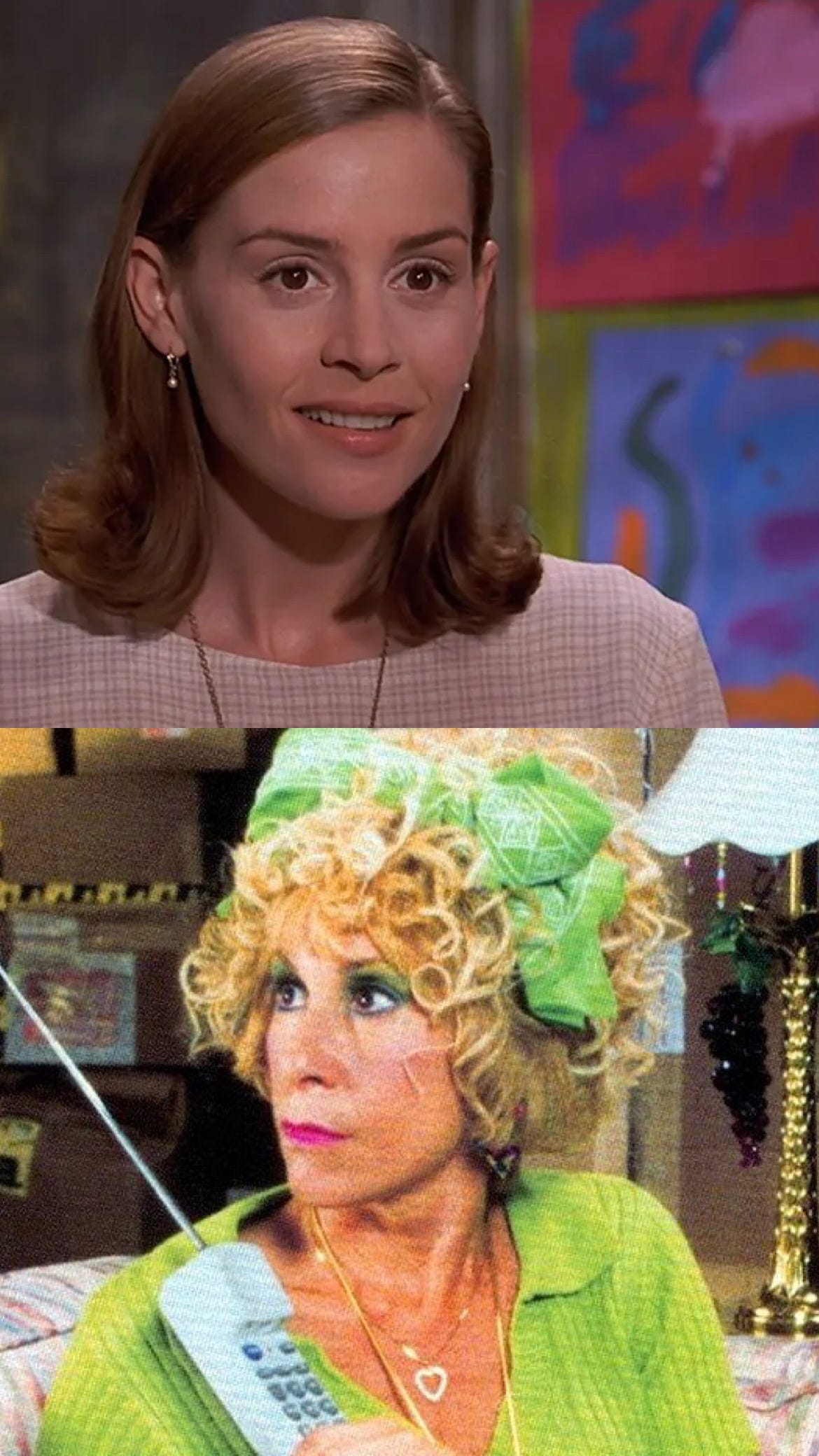

Mr. and Mrs. Wormwood’s attire is antithetical to their daughter’s, emphasizing Matilda’s mental and physical alienation. They wear tacky checkered and leopard-print patterns, flashy neons, and maintain overly-styled hair to symbolize their gaudy personalities and shared sense of vanity.

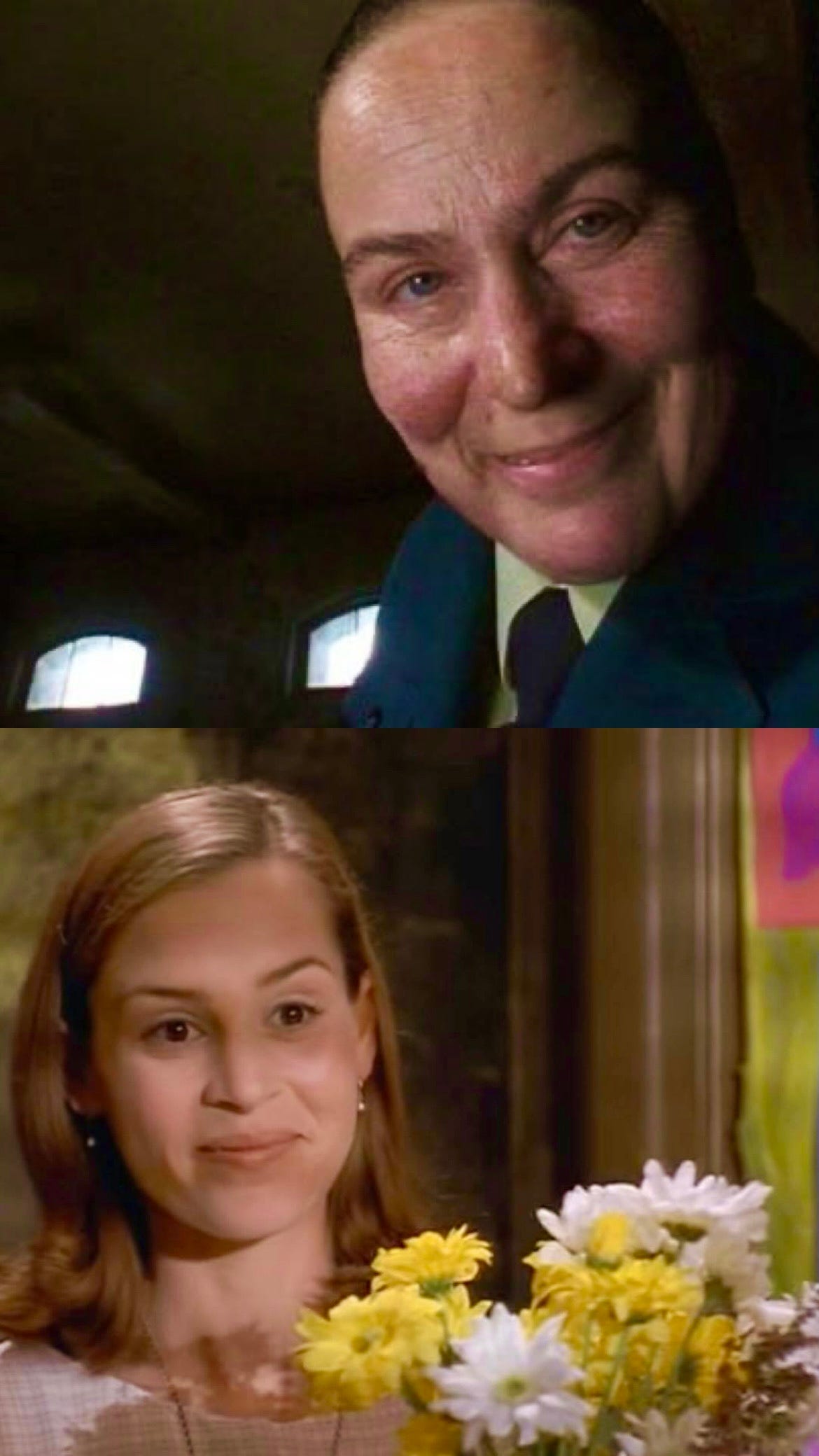

Miss Trunchbull is one of the few blazons that Dahl details in words rather than pictures. Accordingly, Devito’s Miss Trunchbull remains accurate to Dahl’s text, wearing military colours and sporting the same “brown [...] smock,” “wide leather belt…[and] enormous silver buckle,” “bottle green” breeches, “stockings,” and “flat-heeled brown brogues”, which showcase her androgynous, athletic build (116). Matching her illustration, her hair is tightly pulled into a bun, highlighting her rigid standards and the tight ship that she runs (119). Devito’s Miss Trunchbull remains textually accurate in all aspects, mirroring her characteristic reluctance to change.

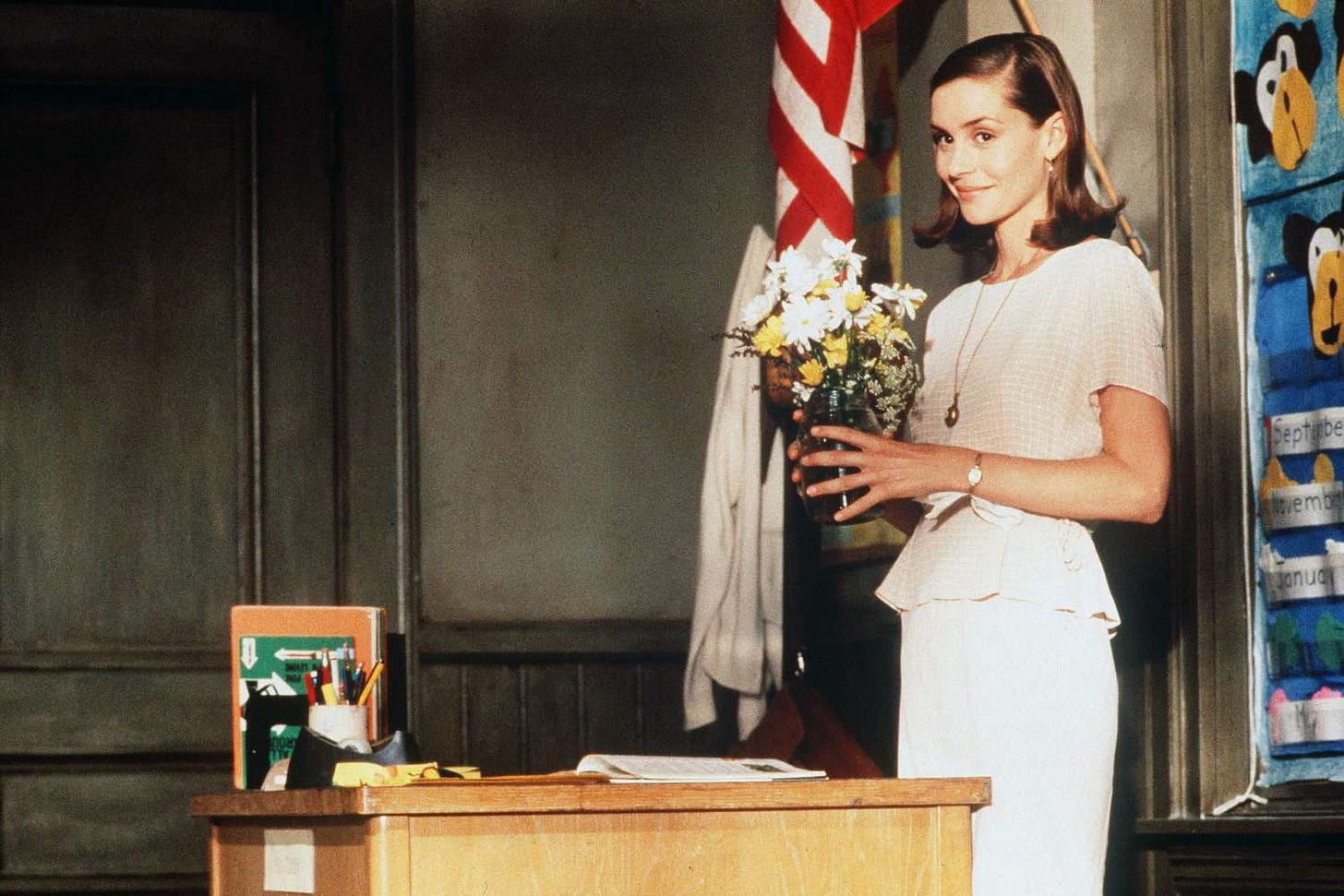

Finally, Devito paints Miss Honey in either harmony or discord with others. Miss Honey’s short, tamed bob echoes Matilda’s haircut to illustrate their similar minds, deep bond, and shared desire for control. Her pastel, neutral colour palette affirms Miss Honey as sensible and unassuming in comparison to the other wacky adults, and a calm, balanced presence to her students.

With subtle make-up and natural honey hair, she contrasts Mrs. Wormwood’s “dyed platinum blonde” hair and “heavy make-up”, thus establishing a visual dichotomy between the female figures in Matilda’s life (31). While Dahl’s text provides brief descriptions of appearances, Devito’s costuming accentuates their personalities and relationships with one another through costumes and colours.

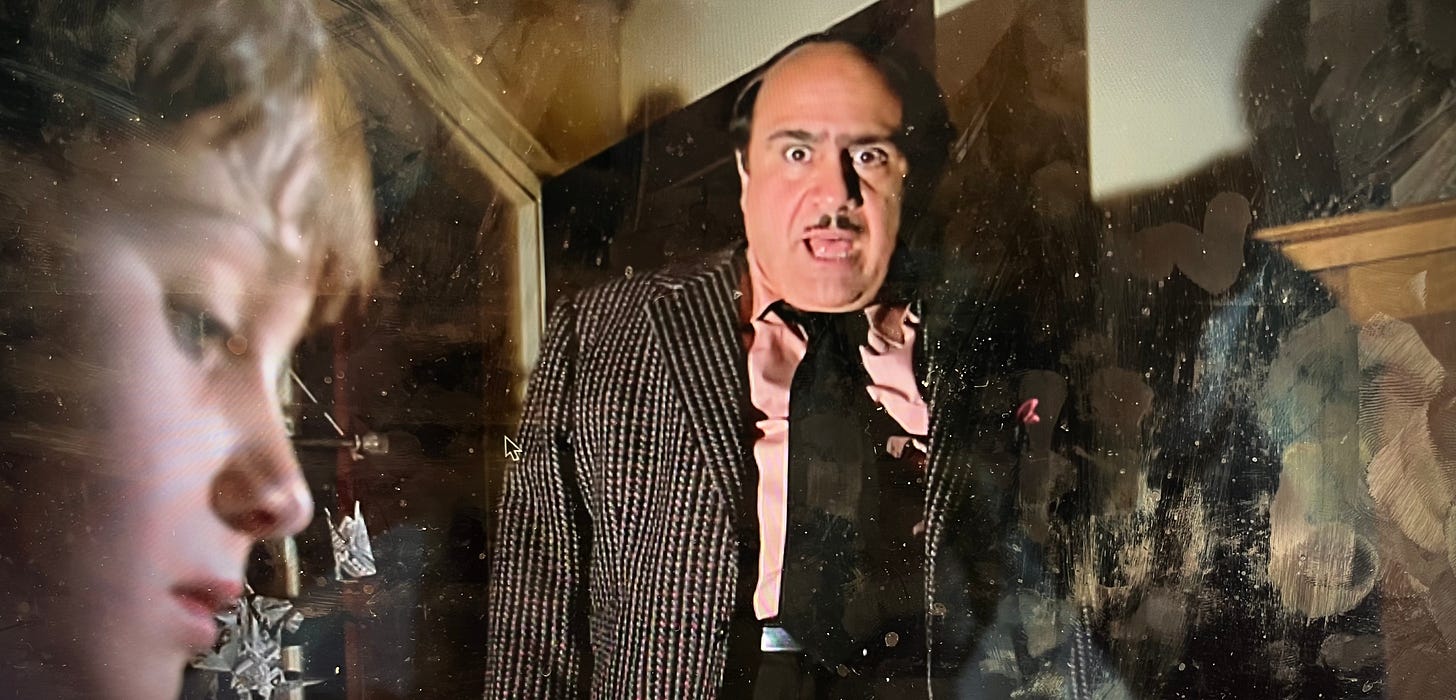

Devito’s cinematography during scenes of conflict through lighting and camera angles emphasizes Dahl’s themes of power inequalities and child-adult hierarchies. Low and high-angle shots are repeatedly utilized in interactions between children and threatening adults. As Mr. Wormwood yells at Matilda for reading, Devito opts for a low-angle shot to assert his attempts at overpowering his daughter. With this low angle, viewers are placed at eye-level with Matilda, seeing her father through her frightened perspective as he towers over her, demanding, and pointing his finger (Devito 00:07:43).

Matilda’s room is solely lit by her reading light, highlighting that reading is a source of light in her life with her bedroom being a safe space to be truly herself and do as she pleases (00:07:59).

However, her reading lamp casts a shadow of Mr. Wormwood behind him as if he and his shadow are intruding her safe space by overpowering Matilda and ganging up against her (00:07:43).

Similarity, low-angle shots are chosen in disciplinary scenes between students and Miss Trunchbull such as when she berates Bruce and threatens Amanda (00:38:00-00:40:22), (00:26:31). These scenes spotlight Miss Trunchbull’s superiority complex over children as she physically and mentally looks down upon her students in these shots. These angles allows the camera to uphold Miss Trunchbull’s hierarchies and perceived sense of power.

High-angle shots create an equally dominating effect by placing the camera from the adults’ point of view. During another argument, the camera is behind Mr. Wormwood terrorizing Matilda again, building up harrowing suspense by not showing Mr. Wormwood’s facial expressions. As high-angles from behind showcase a character’s back, viewers are unable to empathize with the character as their face is unobservable which adds to a villain’s authoritative persona. This angle allows viewers to see Matilda’s emotional responses but the high camera makes it impossible for her to meet its gaze or try to level with, rendering the victims in these shots powerless and surrendering to both their tormentor and the camera (00:16:09).

In contrast, Miss Honey is shot at eye-level with the children, refusing to tower over them, instead, kneeling to meet their gaze.

Whereas lighting in scenes with Mr. Wormwood and Miss Trunchbull are shadowed, dark, and claustrophobic, Miss Honey’s scenes hold an abundance of natural light, often shining upon her face. Through purposeful camera angles and lighting choices, Devito focalizes the power dynamics that work for and against Dahl’s characters.

Arguably the largest of Devito’s deviations from Dahl’s book lies in Matilda’s usage of her powers and his ending. These decisions spotlight Matilda’s maturation and build upon her developing agency rather than removing it. In Dahl’s text, Matilda only accesses her psychic energy three times and is restricted to objects that she directly focuses on like the newt-filled water glass and a chalk piece. There is hardly any evolution as shortly after she has learned of these ‘miracles’, she is stripped of them entirely. Dahl’s Matilda concludes with Matilda losing her powers after entering advanced classes, stating that her magic resulted from “tremendous energy bottled up in [her head] with nowhere to go” (Dahl 345). This resolution strips her of the agency her powers just newly provided her, ultimately ridding her of the potential journey to grow and regulate this ability. In Devito’s Matilda, he grants Matilda more freedom as there are no limits to what she can do with her powers varying from blowing up TVs to telekinetically making herself a bowl of cereal (Devito 00:20:50-00:21:30), (01:09:10-01:09:36).

This capability creates a learning lesson for Matilda as she initially can only harness her powers when angry but teaches herself to summon and control them at will, bolstering her self-control. Matilda’s brilliance is reaffirmed rather than retracted through Devito’s revisions. In Dahl’s conclusion, Matilda is “glad” to have lost her powers, explaining that she “wouldn’t want to [live] as a miracle-worker” (Dahl 345). However, in the book, she was never given the freedom to learn to apply them lightheartedly, as Devito’s Matilda was. Contrary to her textual counterpart, Devito’s Matilda appears glad to live with her powers as she does not feel obligated to work miracles. Instead, Matilda utilizes them to make herself and her loved ones happy as evident through the film’s finale where she beamingly brings a book telekinetically toward her and Miss Honey to read (Devito 01:36:06-01:36:28).

In Danny Devito’s Matilda, he builds upon the characters and themes created by Roald Dahl and advances them with features uniquely made possible through film. Dahl’s black-and-white illustrated characters are brought to life with Devito’s creative costuming and colour palettes to enlighten characterizations and cultivate nuanced, visual dichotomies between characters. Since the printed text is unable to pan up and down or showcase various angles, Devito dramatizes textual power dynamics by toying with cinematic techniques. Finally, Matilda gains maturity in Devito’s new ending as she learns to healthily navigate her powers and accept herself for who she is—magic and all.

thank you for reading my literary library. your support never goes unrecognized or unappreciated. as always, if you have anything to add to the conversation: comments, questions, praise, contrarian perspectives… don’t hesitate!

from my heart to yours, kara koblanski. <3

Dahl, Roald. Matilda. Puffin, 2023.

Matilda. Directed by Danny Devito, Sony Pictures Releasing, 1996.

I always loved this movie but previously have only experienced it, rather than analyzing the techniques used to emphasize the characters and dramatize the story. Thoroughly enjoyed your examples and wonder if you couldn’t re-analyze the movie via miss honey’s techniques as they relate to your (previous post) personal and evolving pedagogy? Trunchbull serves as a great antithesis to this as well!

10 thumbs up 👍🤩 Such awesome writing Kara, your outstanding in summing up Matilda 👏